Francois de Paris and the Jansenist Miracles – Antique Engraving

Francois de Paris: Jansenist Miracles

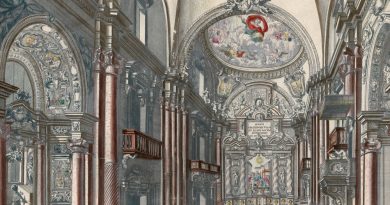

This unique 18th Century engraving commemorates the life and miracles of the Jansenist deacon (diacre) Francois de Paris (1690-1727) and the convulsionary movement which developed at his tomb.

The Fascinating Story of Francois de Paris and the Jansenist Miracles

In their 1825 book “The History of Paris from the Earliest Period to the Present Day” A & W. Gagliani describe the deacon thus:

“Francois Paris, son of a councillor of the Parlement, relinquished, in favour of his brothers, all right to his paternal inheritance. He was a deacon whom humility induced to decline the priesthood, and, renouncing the world, he retired to a house in the faubourg Saint Marcel. There, devoted to exercises of penitence and charity, he employed himself in knitting stockings for the poor, whom he comforted and instructed.”

The Jansenist movement was founded a puritanical branch of Dutch Catholics in the early 17th century. The movement became popular in France, but it diverged from standard church doctrine putting its practitioners at odds with both Rome and the Monarchy. Francois de Paris sided with the Jansenists in their opposition to the Bull Unigenitus which condemned the Biblical interpretations of the French Jansenist Theologian Pasquier Quesnel.

Francois de Paris died on May 1, 1727 in the midst of the debate over the Bull, and was buried in the parish cemetery of Saint-Medard in Paris.

Soon worshippers began to gather at his tomb and reported miraculous healings and events – this engraving documents these healings with the specific names and dates on which they occurred. Each leaf represents a miracle.

Mourners at the tomb also began to go into strange convulsions, and empassioned followers filled the streets writhing as though in a trance. This phenomenon of the “convulsionaries” went on for as long as two decades and was famous throughout Europe. According to some records as many as 3000 volunteers were required to restrain the crowds, and to restrain the women some of whom howled or barked like dogs, or became indecently exposed in the midst of their fervor.

The astonishing sight of the convulsionaries – including many attractive young women – around the tomb became in itself a tourist attraction.

The Church was alarmed at the developments, but found itself in a difficult bind since it would mean condemning what appeared to be a series of miracles. This difficulty was summed up in a couplet that began to circulate in Paris: *

“De par le roi defense a Dieu

de faire miracle en ce Lieu”

“By the Kings Order

God is Forbidden to Make Miracles

In this Place”

Examples of some of the texts on the leaves about the portrait:

“Un enfant de 10 ans de Monsieur Bucheron marchand a Vendome aveugle, geuri en Octobre 1731 aux nouvelles ecclesiastiques de 1732.”

“Soeur Anne Therese Yone de St. Benoist religieus professe des Crodelieres de Neuchatel en Normandie depuis longtemps percluse de ses jambes gueri le Vingt-un Septembre 1732 aux Nouvelles Ecclesiastiques 1731.”

Read French Wikipedia Article about the Convulsionnaires de Saint-Médard

* Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

By Marijke Gijswijt-Hofstra, Brian P. Levack